Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) comprises nearly 11,000 five-digit alphanumeric descriptors which succinctly represent medical procedures. Whether employed for routine check-ups or complex surgeries, CPT codes are essential to medical documentation in the United States.

CPT facilitates the exchange of information between healthcare professionals. It allows for the identification of trends in medical treatment, provides the basis for cost comparisons, and enables the study of variations in access to treatment options by geographic region and socioeconomic class.

Most importantly, CPT serves as the linchpin in communication between healthcare providers and payers, ensuring that services rendered can be accurately documented and billed and that providers are properly reimbursed.

The American Medical Association (AMA), which maintains and holds the copyright on CPT, describes it as “the language of medicine today.”

Development of CPT

The AMA introduced the first version of CPT, with approximately 3,500 mostly surgery-specific codes, in 1966.

It was a defining period in American healthcare. A growth in employer-based health insurance after World War II and the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid had given a record number of Americans access to healthcare. At the same time, medical advancements, ranging from open-heart surgery and organ transplants to the development of vaccines for childhood illnesses were offering new options for disease treatment and prevention.

Between the burgeoning number of patients and the pace of medical breakthroughs, it became impractical for individual providers to represent the treatments they rendered in their own words. In 1964, a representative of the AMA described the medical terminology of the era as “colored with hearsay and superstition, tangled and distorted in whimsical narrative.”

Above all, medical terminology was inconsistent. Providers, payers, regulators, and researchers alike recognized the need for standardization in medical documentation.

There was also a new factor at play in American medicine. In proffering CPT as a common medical nomenclature, the AMA cited the “increasing use of computers in claims administration and statistical analysis.” Automation in healthcare administration all but demanded a uniform lexicon for healthcare billing.

Adoption by federal agencies

The AMA was one among dozens of organizations proposing medical coding systems during the 1960s. Notably, the National Association of Blue Shield Plans, which subsequently became the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, also formulated a coding lexicon. The persistence of CPT today, while the other options have been forgotten, largely reflects choices the federal government made.

In 1977, Congress directed the Health Care Finance Administration (HCFA, now the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]) to establish a procedural code for use in Medicare and Medicaid billing. Rather than create its own, the agency contracted with the AMA for the “non-exclusive, royalty free, and irrevocable license to use, copy, publish and distribute” the CPT.

HCFA required the use of CPT in billing for Medicare Part B services in 1983 and in Medicaid billing in 1986.

The passage of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 imposed requirements specific to the use of CPT in private payer contexts. Charged under HIPAA with identifying national standards for the transmission of any electronic healthcare information, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) identified CPT and the HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) as procedure code sets in 2000.

Since then, CPT has undergone significant transformations to keep pace with medical developments. Not only has the system expanded in terms of volume, but its granularity has also become more complex, encompassing an expanding spectrum of medical procedures.

A practical explanation of the use of codes

As CMS notes, “(c)lear and concise medical record documentation is critical to giving patients quality care and getting correct and prompt payment for services.”

Healthcare providers and their staffs use CPT codes to document medical services rendered. In the process of billing, coders review medical records to determine which CPT code(s) properly reflect the nature of a medical visit or procedure. These codes are included on claims submitted to insurance companies, allowing for standardized communication of the procedures performed, as well as the expected reimbursement.

The universality of CPT facilitates information exchange, enabling accurate billing and reducing the likelihood of errors.

Categories

There are three category of CPT codes.

- Category I includes codes for evaluation and management, anesthesiology, surgery, radiology, pathology and laboratory, and medicine.

- Category II codes, also known as “tracking codes,” are optional and used in measuring performance improvement.

- Category III codes are temporary codes assigned to emerging practices or new technologies and remain in effect for a maximum of five years. While policy allows for the renewal of category III designation, procedures are usually transitioned to Category I or archived after five years.

Coding for E/M

Most services provided by primary care physicians, emergency room physicians, and specialty care physicians in an office or outpatient setting are characterized by evaluation and management (E/M) codes.

Office visits are typically coded with a 992XX taxonomy in which the fourth digit specifies whether the patient is new or established. For example, for new patients, the fourth digit would be “0” (99202, 99203, 99204, 99205), while for established patients the fourth digit will be “1” (99212, 99213, 99214, 99215).

The complexity of an office visit is represented in the fifth digit of these E/M codes with higher numerical values correlated to more medically complex cases and/or cases requiring additional time. As an illustration, an established patient seen for a simple complaint would be coded as 99212, while an established patient seen for a life-threatening acute or chronic illness would be coded as 99215.

Notes in the medical record must support the code assigned to the patient visit and, at a minimum, must document the length of the visit and the level of medical decision making required of the healthcare provider.

CPT codes can reflect varying levels of complexity, and it is possible for a single CPT code to cover multiple procedures. For example, CPT 21046 (Excision of benign tumor or cyst of mandible; requiring intra-oral osteotomy e.g., locally aggressive or destructive lesions) could increase in complexity to code 21047 (Excision of benign tumor or cyst of mandible; requiring extra-oral and partial mandibulectomy [e.g., locally aggressive or destructive lesions]). In this case, the coder would choose the code indicating the complexity of the procedure performed to the highest level of specificity.

Modifiers

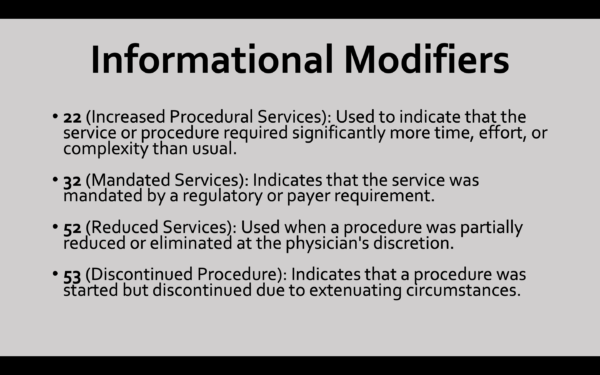

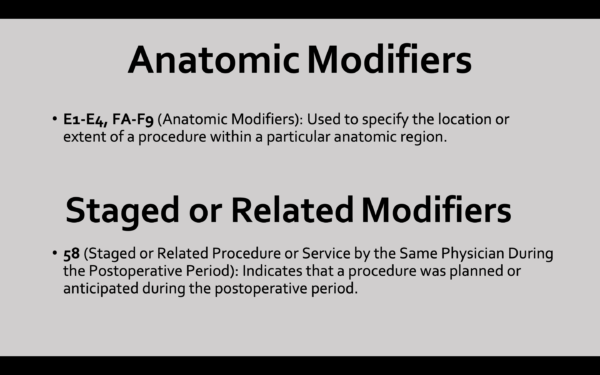

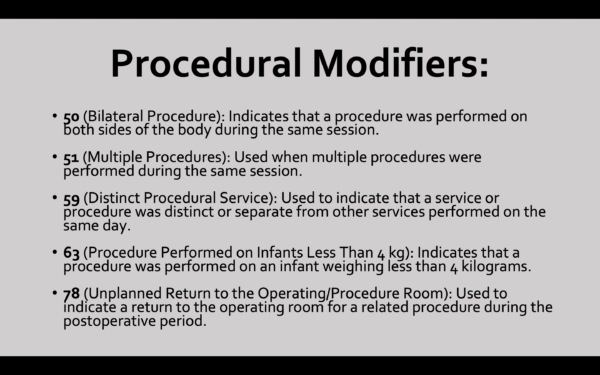

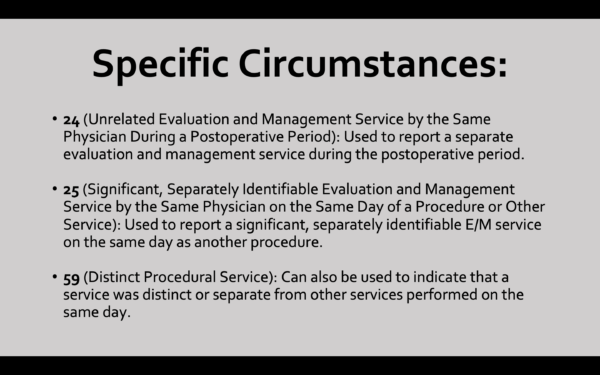

Two-digit modifiers may be affixed to the end of certain CPT codes. These modifiers are composed of two numerals, two letters, or a combination of numbers and letters.

Modifiers can be used to indicate the side of the body a procedure was performed. For example, in ophthalmology, the E3 modifier would specify the “upper right, eyelid,” while E4 would specify the “lower right, eyelid”.

Modifiers may also be used for the purposes of clarification. In the case of a patient seen by the same provider twice in one day for two distinct complaints, the “25” modifier could be used to designate the second visit as a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service.” Similarly, the “59” modifier can be used to indicate that multiple conditions or sites were treated and the “76” modifier is used when the same procedure is reported more than once on the same day of service.

As Applied Policy previously reported, modifiers may be required for regulatory compliance as in the case of the JZ modifier as an attestation that no drug from a single-use dose or vial was discarded in the course of a procedure.

More than one modifier can be used with a single code, with modifiers specific to payment placed before informational modifiers. While the AMA reviews and updates modifiers annually, individual payers may specify different uses, so coders must be familiar with how each payer uses each modifier.

Application and Code Development Process

There is a Medicare reimbursement rate associated with each CPT code; procedures without CPT codes are not eligible for Medicare reimbursement. This makes assignment of CPT codes critical for providers and manufacturers.

The process of code development is a meticulous undertaking, involving collaboration between the AMA and an array of stakeholders, including physicians, payers, and governmental entities. Although anyone can propose updates or revisions to the CPT, modifications can only be made by the AMA’s CPT Editorial Panel (The Panel).

The Panel has 21 members, 12 of whom come from the over 120 national medical specialty and other societies comprising the Federation of Medicine. It has one seat each for the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, America’s Health Insurance Plans, the American Hospital Association, an umbrella organization representing private healthcare insurers, and an at-large organizational member.

The Editorial Committee is informed by the larger CPT Advisory Committee, whose members come from national medical specialty societies, and the Health Care Professionals Advisory Committee, which represents allied health professionals.

Proposals for new codes or changes to existing codes undergo rigorous scrutiny. The Panel, which convenes three times a year, considers factors such as medical necessity, technological advancements, and how frequently a procedure may be performed.

Panel meetings are hybrid and open to the public, although registration is required. Meeting agendas are typically available 10 weeks before scheduled meetings. Individuals or entities who may be impacted by code changes may register as interested parties, review non-proprietary information associated with a specific change, and provide comments on the proposed change.

Criticism and responses

Despite offering a critical standardization in healthcare communication, CPT is not without critics.

One complaint stems from the sheer volume of codes, with some arguing that the system has become overly complex. Critics contend that the granularity of codes can lead to administrative burdens for healthcare providers. Navigating through thousands of codes, they say, demands time and expertise, potentially diverting attention from patient care.

A study published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine in 2017 found that CPT and the rules associated with its use failed to capture the “cognitive work” performed by family physicians. The study’s authors stated that “either the CPT codes and their associated rules should be updated to reflect the realities of family physicians’ practices or new billing and coding approaches should be developed.”

Acknowledging these concerns, in 2022 the AMA announced modifications to E/M coding designed to relieve “physicians and care teams from time-wasting administrative tasks that are clinically irrelevant to providing high-quality care to patients.”

Another criticism pertains to the speed of code updates in response to technological advancements. As the landscape of healthcare continues to evolve, new medical procedures and technologies are constantly emerging. Detractors argue that the current process of code development and updates might lag, hindering accurate representation of cutting-edge medical practices.

While CPT may have previously failed to keep pace with medical breakthroughs, the Editorial Panel has been proactive in the anticipation of a growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine. In 2021, it adopted the Taxonomy of Artificial Intelligence for Medical Services and Procedures as an appendix to the CPT 2021 to establish a common language for describing new procedures completed or augmented by machines or software.

Some have described the AMA’s management of CPT as a monopoly, questioning whether the group should be allowed to profit from a coding nomenclature when its use is mandated under federal law.

To date, the AMA has prevailed in court. In Practice Management Information Corp. v. American, perhaps the most famous challenge to the AMA’s copyright, the court ruled that the AMA “did not coerce the HCFA to choose one code over others or to accept the AMA’s royalty-free license to use the CPT.”

Although critics were dissatisfied, the CPT has undergone more than two dozen revisions since the Practice Management case, cementing its position as the common language of American healthcare.

CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. All specific references to CPT codes and descriptions are copyright of the American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

The choice of modifier depends on the specific circumstances of the medical service or procedure being reported and is important to accurate coding and billing. The following examples of modifiers are for purposes of illustration only. Different payers may employ modifiers differently, always confirm with your contracted payer before using modifier(s).