The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, commonly known as the ICD, is a globally recognized system of medical data management. Developed, maintained, and copyrighted by the World Health Organization (WHO), the ICD offers a comprehensive framework for classifying diseases, medical conditions, and other health-related phenomena. Its tenth iteration is referred to as the ICD-10.

More than 114 countries use the ICD to monitor mortality (deaths) and morbidity (disease and injury). Beyond being a critical epidemiological tool, the ICD serves as the basis for healthcare planning, resource allocation, and health policy development in many nations.

In the United States, we are most familiar with the ICD-10-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification), a U.S.-specific adaptation of the ICD-10 which is essential for establishing and documenting the medical diagnoses which justify the clinical interventions for which healthcare providers bill.

HISTORY OF CLASSIFICATION

The ICD grew out the first International Statistical Congress of 1853, which charged William Farr of England’s General Register’s Office (GRO) and Jacob Marc d’Espine, of the Societe Medicale d’Observation in Paris, with developing a single international system for classifying disease. Their collaboration was the genesis of the International List of Causes of Death, adopted by the International Statistical Institute in 1893. By its sixth revision, the list was retitled The Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death.

The WHO has overseen the maintenance and updating of the ICD since 1948. Today the ICD is one arm of the WHO’s Family of International Classifications Network (WHO-FIC), which also includes the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and the International Classification of Health Interventions.

THE ICD-10-CM

The WHO has authorized a limited number of countries to modify the ICD for use within their borders and jurisdictions. In Australia, for example, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) is used for funding and service planning. Germany’s ICD-10-GM serves as the basis for the country’s remuneration and financing systems and Thailand’s ICD-10-TM is available in both English and Thai versions.

In the United States, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is authorized to oversee modifications to the ICD in cooperation with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). With the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) they comprise the Cooperating Parties for the ICD-10-CM.

There can be a significant lag time between the effective date of an ICD release and the adoption of its modification the United States. For example, the ICD-10 was adopted by the WHO in May of 1990 and available for use at the beginning of 1993. However, the transition from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM in the United States was not accomplished until October 1, 2015.

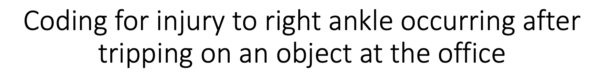

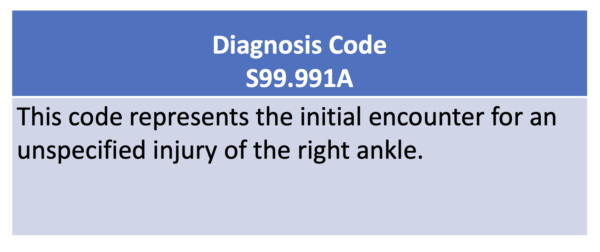

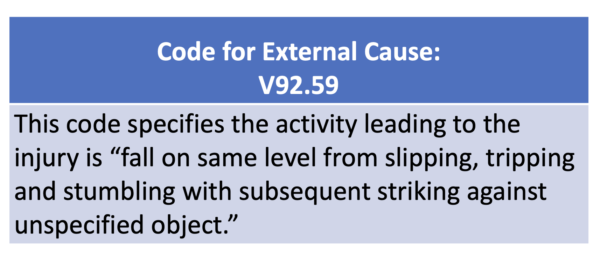

THE PROCESS OF CODING

Medical coders review medical records, including physician notes, laboratory results, and diagnostic imaging reports, to identify and extract pertinent information about a patient’s diagnosis. With 22 chapters, the ICD-10-CM provides a comprehensive set of alphanumeric codes that correspond to specific medical conditions, allowing coders to accurately classify and categorize diagnoses. Individual codes may be three, four, five, six, or seven characters in length.

The process involves analyzing the patient’s symptoms, clinical findings, and any relevant documentation to assign the appropriate code, ensuring that healthcare providers, insurers, and other stakeholders have a standardized and universally understood language for communication.

The ICD-10-CM also allows for coding to describe signs and symptoms when a provider has not confirmed a definitive diagnosis.

REGULARLY UPDATED

Historically, the WHO has released complete revisions of the ICD about once every ten years. It also specifies processes for updating current versions of the classification as necessary.

In the United States, anyone can petition the ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance Committee for a revision to the ICD-CM. Requests may include additions, deletions, or clarifications.

Modifications approved by the committee typically reflect differentiation in existing diagnosis, recognition of new conditions, or classification of pathologies arising from new behaviors. As an example, recent additions to the ICD-10-CM have included codes specific to encounters related to the use of e-cigarettes or vaping.

Changes may also reflect changing social attitudes. Among the requested updates to the ICD-10-CMS supported by the AHIMA for implementation this year is a change in language regarding injuries from firearms. The from “accident by unspecified firearm” to “assault by unspecified firearm.”

While updates have previously been released once a year, with changes effective on October 1, in 2021 CMS announced a shift to semiannual releases with the additional implementation date of April 1.

RAPID RESPONSE: COVID CODING

The ICD can be rapidly updated in exceptional circumstances. This typically involves the use of special purpose “U” codes. In February 2020, the WHO activated emergency codes for confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 (U07.1) and clinical or epidemiological diagnosis (suspected or probable) of COVID-19 (U07.2). In 2021, codes were activated for both COVID-19 immunization (U11) and adverse reaction to COVID immunization (U12). Long COVID has also been recognized with the code “Post COVID-19 condition, unspecified” (U09.9).

The WHO can also make rapid revisions in response to cultural concerns. Last November, the organization cited “racist and stigmatizing language online, in other settings and in some communities” in announcing its decision to transition from the use of the word monkeypox to the new term Mpox. A change in the online version of the ICD-10 was accomplished in days.

ACCOUNTING FOR SDoHs

The growing understanding of the role which social factors play in shaping health outcomes has necessitated a means for documenting social determinants of health (SDoHs) in medical records. As a result, the scope of the ICD has been expanded beyond traditional disease classifications.

Chapter 21 of the ICD-10-CM lists coding options for “Factors influencing health status and contact with health services.” Since 2016, these “Z codes” have included coding specific to a patient’s socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances.

Current Z codes provide for documenting a variety of SDoHs, including education and literacy, housing circumstances, and employment status. According to CMS, the most reported Z code is Z59.0, which is specific to persons experiencing homelessness.

Public health advocates and the private sector are contributing to the expanding list of Z codes. UnitedHealthcare and the American Medical Association report collaborating on the development of new codes for SHOHs, and the AHA has a campaign alerting providers to the availability of codes for human trafficking.

While most coding must be based upon clinical documentation provided by a patient’s provider, coding for SDoHs may be made based on reports from any member of a patient’s care team, including community health workers, intake personnel, and discharge planners. Z codes may also be included based on self-reporting with the sign-off of a clinician.

Adoption of the use of Z codes has been slow. They were included on less than two percent of Medicare fee-for-service claims in 2017. Research suggests that they are more likely to be recorded on hospital admissions or office visits related to mental health or substance use, despite the fact that SDoHs are directly linked to physical health, as well.

CRITICISM

The ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM are not without critics.

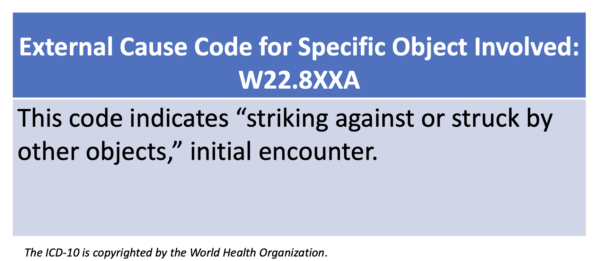

Their systems of classification have been faulted as being too specific with codes for such wide-ranging, if infrequent, events as being “struck by a turtle” (W59.22XA),“injured in an opera house” (Y92.253), or “other contact with a chicken” (W61.39), while underrepresenting SDOHs.

Some specialty groups believe that their areas of focus are under or misrepresented by the available classifications. For example, pain specialists argued that the ICD-10-CM did not allow for adequate documentation of chronic pain. Some behavioral providers have said that the psychiatric diagnoses in the ICD-10 are “diagnoses are neither valid nor of much practical use” and exist to justify treatment and payment. In fact, a Danish study of ICD coding for psychiatric disorders found that 16 codes accounted for over 50 percent of diagnoses, and there are over 380 options.

Regular revisions of the ICD present the possibility for coding errors. While these may impact a provider’s bottom line, they can also have consequences for public health studies. In 1949, for example, researchers observed a promising reduction in the rate of deaths associated with diabetes. But closer review of the data showed that it was related to a change in coding between the seventh and eighth revisions of the ICD.

There are administrative burdens associated with the adoption of each revision of the ICD. In 2011, in anticipation of the transition from ICD-9-CM which had less than 18,000 codes to ICD-10-CM, the federal government acknowledged that it “would be a difficult time.” The Rand Institute estimated that the changeover would cost providers as much as $1.15 billion total, with $5 million to $40 million a year in lost productivity. In recognizing the burden, CMS issued a final rule adjusting the medical loss ratio for payers.

COMING NEXT: ICD-11

Payers and providers will need to brace for another change in the coming years.

In 2019, the 72nd World Health Assembly approved the ICD-11. The revision includes approximately more than 120,000 codable terms, a remarkable increase over the ICD-10. The WHO emphasizes that the ICD-11 was developed for a digital world, with a coding algorithm which can interpret more than 1.6 million terms.

More than 60 countries have already begun implementation of ICD-11. However, there is not yet a timeline for its adoption in the U.S.

In 2021, the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) advised Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Xavier Becerra that the department needed to undertake research to determine how to transition to ICD-11 and should keep the healthcare industry apprised of a timeline for the inevitable transition.

Although NCVHS had received 19 responses to its Request for Information for the adoption of ICD-11 as of this summer, the timeline for the transition has yet to be provided.